Unmuddied, Ludovic Slimak essays the Naked Neanderthal

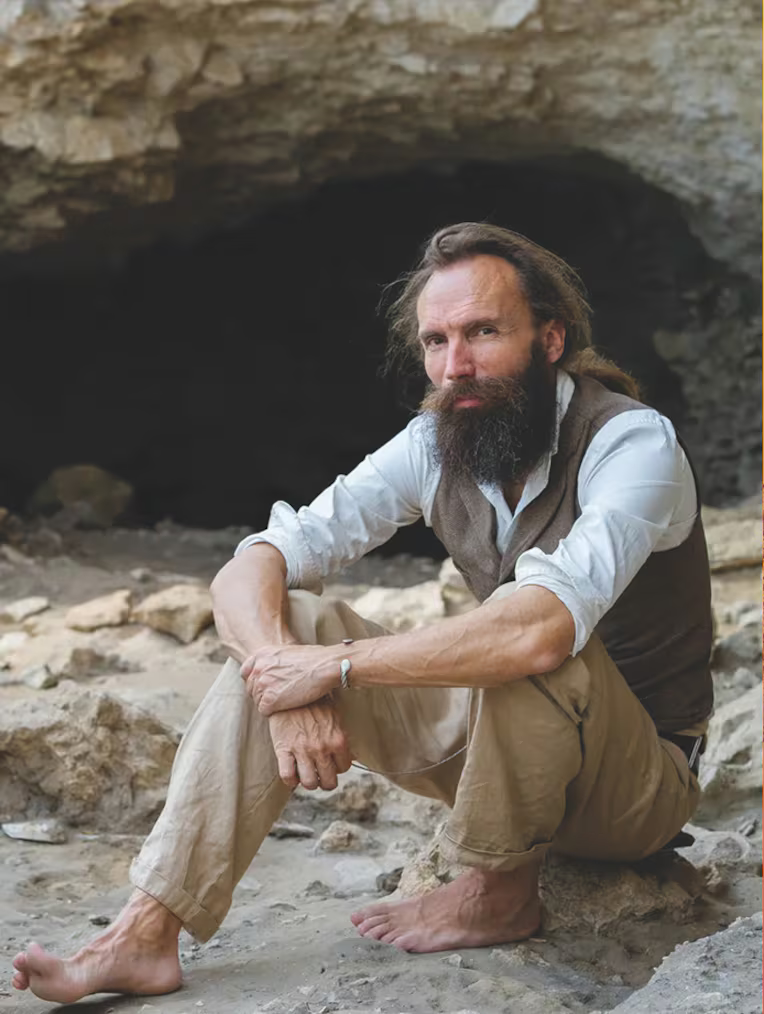

This is the author in their natural habitat, but curiously unmuddied or dusted, from the inside of the dustjacket of the book The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature. The title riffing on Desmond Morris’ The Naked Ape (tell me, if you’re under 40 would you have any idea?) but the nakedness here refers to removing our H. sapiens investitures, our projections, seeking to unclad our investments, our skin in the game, remove all that baggage from Homo neanderthalensis, and not the clothes that reveal our nudity.

There is no new 'understanding' here, perhaps we can blame the publisher for the colonic subtitle. And while knowing we don't know is not always obvious, it has occured to some of us for the longest time.

Ludovic Slimak is basically saying we cannot know them, thus we cannot assume whether or not they are like us, nor by how much, nor how little. We do not have enough evidence for starters.

He has the mud of experience to prove this.

The book is an excellent essay, or lesson, in actively suspending judgement. It shows that a blur is arguably a type of understanding, if rarely accommodated in the world.

The essay assays, and so advises us to avoid, the rash favour of our perspectives with which we address this question, both rose-colour glasses and the demon eyes. I would add that this is good advice for most questions we worry at.

Besides this most valid point, the author does feel with the evidence now collected, it likely follows, that, they probably are not like we can even imagine them to have been. It is possible that they did not have even some element of how we perceive ourselves, unlike Star Trek aliens, or fantasy races of elves & dwarves, which have some Sapiens element turned up to 11.

No, but… —we cannot say it was not either. If there is a difference so great we cannot imagine it, we may never know that, let alone understand them if they stood before us, even if we could meet them… —again. Even if we carry their DNA in or own lines.

I like this position.

This will run true for those other human species, Denisovans and the ghost populations in the taphonomy of our DNA, for whom we have even less material evidence, especially material culture which might betray hints of the world they inhabited. We Sapiens by contrast world away culturally, variously, politically, religiously, artfully in increasing horns of plenty.

The bigger question is how may types of modernity could there possibly be available in a fitness landscape there was once, and not just as a variation of Thomas Nagel’s What is it like to be a bat?

But how human is Homo sapiens, or rather how much of our own worlding is required to be human, how common is this in Homo as a genus, and how much of us is an over-extension, and how different can various humanities can actually be. I.E how much can the Homo genus diverge from whatever palaeolithic commonality we came from.

How can we guess at any of that when we cannot even map the range of possibilities?

Even that question probably assumes too much.

How do we even begin to ask these questions?

It refocuses the debate and tackles their material reality head on. It asks questions about notions of the historical and ethological truth of populations of which we know little, and which we urgently need to stop dressing up as ourselves. [page 148]

Especially, I would argue, when we don’t know what we are, or at least, which bit of who we are, is what we are.

Crossposted at substack.com. And postscript too.

References

Nagel, Thomas. 1974. ‘What Is It Like to Be a Bat?’, The Philosophical Review 83(4): 435. [via https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Nagel_Bat.pdf]

Gooch, Stan. 1977. The Neanderthal Question. London: Wildwood House. (mentioned in this other post on the clothes we dress our bones with: guilty pleasures of an aquatic ape, Elaine Morgan and a scientific noyau)

Segalov, Michael. 2023, September 10. ‘“I Feel like a Man from Another Era”: Neanderthal Hunter Ludovic Slimak’, TheGuardian.com. [https://www.theguardian.com/science/2023/sep/10/ludovik-slimak-neanderthal-hunter-reinterprets-our-prehistory]

Slimak, Ludovic. 2024. The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature (First Pegasus Books cloth edition.). New York: Pegasus Books. [ISBN9781639366163]

Postscript

When constructing this post I added a profile piece by the Guardian to the photo of Ludovic Slimak that open the post. I skimmed it before adding it as a link in the caption.

Reading it properly a couple of days later I see he is quoted in putting forward more strongly worded in his intuitions (apparent in the book but not to the forefront of the essay on the research of decades). The article puts more biographical detail of his life forward, it is worth reading, and discussing here.

“We might not know much about Neanderthals,” he goes on, “but through what they created, we can see something incredible. When you take Homo Sapiens tools made of flint, spanning tens of thousands of years, in different parts of the world, they’re always the same. Standardised. It can’t be cultural.” There was likely little contact between these different settlements. “There’s something innate within the behaviour of Homo Sapiens – within our behaviour – to act and think in a certain way. It’s in our nature.” Neanderthal crafts, though, don’t share this pattern of standardisation. “Look carefully at Neanderthal tools and weapons. They’re all unique. Study thousands and you’ll find each is completely different. My colleagues never realised that. But when I did, I saw there was a deep divergence in the way Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals each understand the world.”

On humans, he says their selfing and thus worlding is much more outsourced, we do more outsourcing to the group and its networks, Neandertal material culture does not betray that same normative push (which I argue is the worlding urge, the urge to should).

“Their tools and weapons are more unique than ours. As creatures, they were far more creative than us. Sapiens are efficient. Collective. We think the same, and don’t like divergence. And I don’t just mean western culture. Go to any Aboriginal society: there are clear rules and customs, and shared styles of clothing. Expectation to act in a certain manner; to follow regulations.” Our ancestors, he says, lived like this instinctively. “You don’t see that with Neanderthals.” By seeing Neanderthals as a reference point against which we can measure ourselves, Slimak reckons humanity is offered a gift: “We have an opportunity to look in a mirror and see ourselves for what we truly are. To help us redefine, which we must do urgently.”

Slimak then does a bit of Sapiens’ worlding urge shoulding himself onto the rest of us (self-evidence of his arguments I would argue) based on his perceptions of risk, and is the hippie he looks like. I share that bias, but have learned to recognise it for what it might be. The way current libertarians, as only one example, actively refuse, lazy fools that they are.

The question for my writing is how 'Homo sapiens form of human' is the urge to should, and how Homo as a genus is it? How derived is the urge to should on people, on the world, what is this proportion of self/world?

The easy 19th century thing to do, framed as it was by empire and the economic stratifications empires dealt with (slave races, the ethnology of subhumans burdening the colonist) (i.e. what a narcissist would do looking for a hierarchy so they can punch down like a baboon) would be to say they lack our worlding urge entirely, and that make us human humans and Neandertal humans only subhumans at best.

One could respond like Gooch in ‘The Neanderthal question” and say they were perhaps 'just' like a differing us.

These two errors would be to repeat the what Slimak deconstructs in The Naked Neanderthal.

So I will put the continuum of the selfing/worlding proportions as follows (it is very metaphorical because we lack the common language to distinguish it, thus I always defer to poetry which is is usually too idiosyncratic, but I do so at the urge to world the self)(if autistically).

All life, all forms of life that respond in space to gradients of energy flow, that encloses and circulates off, for a time, aspects of that flow, in that new moment the body is born, so that, also by that exclusion, is composed the landscape of their activity. I.E. the movement that encapsulates a homeostasis, composes from the substrates and energy flows a landscape as much as it comprises a body. What distinguishes them, composes them together in their separation (literally a figure/ground).

As these things emerge we get landscapes upon landscapes as we get bodies upon bodies as landscapes and their populations contest the now social substrate as a terrain of their landscapes, forming new bodies anew, and thus new landscapes in those contests.

Are you the landscape? No. Are you your body? Yes. Can you have one without a view of the other? No. To self is to world a proportion of those ratios: from self:world, and world:self.

These are different ratios, self:world and world:self, but we can only see that in their reasonable or reasoned proportions, because they have different vectors and they have thus different histories. For social animals like us the world exists before the self arises, the mother is the world child to the self child, just as the child is parent to the adult. Good thing they have a village to raise the world child.

The ego is not on its own when it is born and bears its new world. It’s own follows from that deep history of evolution, well before the genus Homo elided and forgot the world in shoulding the world on each other, and thus created the collective as an individual error, if successful for a while, and more recent high society’s manipulation of that error, compounding it, such that we have a great deal of difficulty seeing it at all. We have trouble seeing the world as it is. And not just because it doesn’t really exist (much like the self is an illusion) but because we make it up as we please and feel we should. And argue about but feel we should not argue about for fear of our fears, biases which engender the successful (evolutonarily) debate as a noyau, in the first place.

There may be no such thing as society, but there is also no such object as the self. Especially without each other.

Within the greater intensity of the social group, society itself become more a part of living the self. It is a failing on us as social animals to think all groups are the same collective, i.e. that the collective is a type of individual. The error treats the group like an individual thing, regardless of whether this is emergent, planned or instructed by a self- idolatrous god.

This is done by all those who fear its hegemony (anarchists, or egoists) and by those who wish to impose it (Imperials in the name of god or god-emperor) (and libertarians who fear they may not become Emperor so fuck all you losers). The world is the enemy up on which they project their perceptions of risk, thus they cannot see the world, they only see some version of themselves. The naked world is beyond their limited intelligence. Of course, if intelligence is outsourced to the group, the failure by these individuals seeking to impose individuality on the world as a collective, means we are worlding badly. The world takes responsibility for nothing. It is still up to us. Responsibility, unlike causation generally, is a selfing activity. A type of movement. A way to move in the world. Thus the confusion.

The world is not an individual self, this is obvious, what is less obvious is neither is it an individual collective even as we should that error into our visions of the world (groups as tribes, nations, classes, cults, clubs, even family are projected onto the world when we feel we should should something) and why loyalty was invented (to paint over familiarity and closeness) by narcissists to impose those hierarchies of baboon stupidity as the first order of control. By making the collective an individual they suit themselves, both expressed as the lone wolf, or as some incarnation of the god/s, preferably a mono-god, as an avatar of the world/empire/people (the idiotic but coherent one oneness of ein volk etc). The elected king as the will of the people. An error.

The urge to should at base allows us to make errors and move on. To fix those emistakes, make other errors, and have the insured resilience to fix them. Other errors fixing errors creating errors include all the outcomes of the worlding urge: religion, morality, polity, markets, ethics…

The world is the world. We have an urge to should it into existence. It developed in the long ages of the palaeolithic when there were more than one type of Homo species around. Slimak sees this normative outsourcing as a strong marker of Sapiens, where we outsource it with some verve, but we cannot say, even on the evidence of Neanderthal material culture, that Neanderthals worlded any the less, even if they did normative shoulding less. Is any normative urge a necessary requirement of the world? Your biases will inform the debate, but how much of you human biases are the result of that normative urge to should? What is it like to be truly alien?

Even if their world:self and self:world proportions differed, they may not represent basal Homo, and what Slimak and other archaeologists discover and interpret may be just as derived as our verve for shoulding the world onto every damn little thing we notice, except currently, the world itself.

Other posts on evolution can be found at Posts on Human Evolution