'Missing institutions' Douglas & Ney's 'Missing Persons: A Critique of the Social Sciences'

Mary Douglas & Steven Ney. 1998. Missing Persons: A Critique of the Social Sciences, The Aaron Wildavsky Forum for Public Policy. Berkeley : New York: University of California Press ; Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 9780520207523

A copy of Missing Persons arrived in excellent condition, while heading towards 30 years old. Bought in my reading to catch-up with the work of anthropologist by training and social theorist by extension Mary Douglas. This reading continues on (and more later I suspect) from reading I did over 30 years ago. Basically I am getting back into it. It has been on the back-burner for a while. See the linkpost.

First thoughts on having finished reading Missing persons, is that it might as well be called missing institutions. This is because the final sections deal with the social sciences recent disinterest in looking at 'institutions'. Apparently it is a dirty word.

Now there are not quite as many usages people put the word “institutions” to, as they do to the word “culture”, but this means that people are even less aware, especially when engaged in talking past each other by using different meanings.

The usage I like is from Delueze, or I learnt it from reading Deleuze. As I remember it: “Laws increase at the expense of institutions.” This ratio doesn’t tell you what institutions are, but does tell you that the law is not just all about punishing wrong-doers. Sometimes it is about sorting out who gets the loot.

Consider the story about the 'institution' of marriage. Barbarian Europe had no laws that no true Roman would recognize, but it was still a founding institution of society. If not the founding institution.

Laws of marriage came into the picture when the Roman Catholic Church deemed females had souls and so their donations and legacies were acceptable, when it wasn’t clear if the husbands, or their fathers even, should just get everything on the women’s death, despite a will giving a legacy to the church. Apparently there were arguments made by self-made men that if women had no souls, then they not a person, that as legal minor the women’s wills mean nothing… —so they tidied up the institution (and common law) in their favour with some proper Law and Order. Yes women have souls, and so yes, they could give their wealth and land to the church because their wills were legal. All’s good.

That women would give stuff to a Church that was unsure about their personhood is yet another example of the worlding subsidy by those who give, for the common good, if not faith, to those who take us for a ride. (Even if those taking us for a ride think that is doing good.)

It wasn’t really a law for not-rich-&-powerful people, they carried on with institutions they knew, such that their arrangements get called common law marriages.

Marriage, despite being an older institution than the church, was a very late sacrament, and so it was even later, that taking holy orders (do what you are told) as a nun for women, was re-branding as the sacrament of marrying christ.

Which is why I think the gay marriage debate was one of those radical/conservative | conservative/radical moments. A true radical would have used common law to come up with some union|trust innovation, sadly no such creativity was shown. The law's colonisation of the institution was complete, and marriage's definition as a real estate deal is complete.

We will now back out of that rabbit hole.

Douglas & Ney say that the study of institutions has been on the nose for a good while (in the late 1900s) and in part, this was due to institutions being seen as impinging on the person. Institutions fettered the individual to medieval claptrap, metaphysical social ontologies or both kinds of ideology.

The connection here with missing persons is that while the individual is brought to the fore in recent social science, especially economics, which classically pretends to be a science and not social at all, is that their working model of a person is an individual bereft of individuality. That Homo œconomicus (currently no wikipedia mention of Douglas or Ney thereon) has no soul, because it only considers as economic calculating machines, who subjectivity is confined to an agency that pursues self-interest optimally, if not perfectly rationally. In that baseless medieval joke it is some kind of female, i.e. 'fe-male', without faith, without a soul.

Going backwards through the book we pass by bounded rationality (which latterly gave us the word satisficing, as in “the middle-mamagers rule the world by satisficing their arses between what they have to do and what they can actually get their ‘teams’ to do”).

Douglas & Ney have before this introduced the idea of biases in relationship to perceptions of risk, and that institutions develop out of those biases in negotiation, despite each bias preferring particular institutional outcomes (ways of worlding/culture/polity/social ontologies).

There, I have just used institutions to mean those hard rituals and routines we use to get through the day, the week, the season, the year, the life stage. Institutions are expectations hardened in to social reality. Laws just double down on that. Social science like economics who don’t do 'social', do so dangerously (depending on your appetite for risk of course).

Given the recent failure of neo-liberal economic consensus and their Homo œconomicus to end history in the face of narcissistic leadership which will seek to substitute loyalty for the rule of law, perhaps we can look to more institutional work to safe us from the chaos when the centre cannot hold.

So then what souls do individuals have? Do only rich narcissists have souls? Because they are the world?

In the work of Douglas and Ney, these afferent biases are grouped into four types. They do mention that there might be more, or less, depending on one' perspective, and refer to some literature, or fairly tales, to cover that base, but argue that four is quite parsimonious, and I tend to agree.

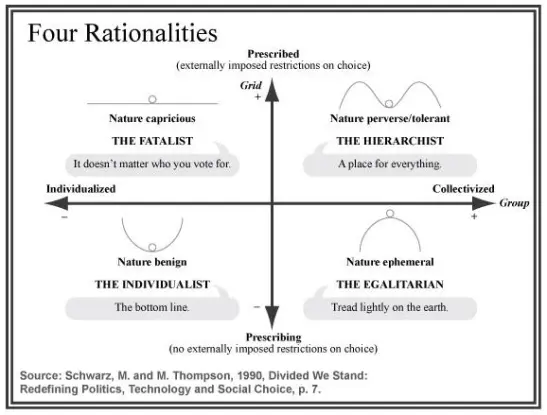

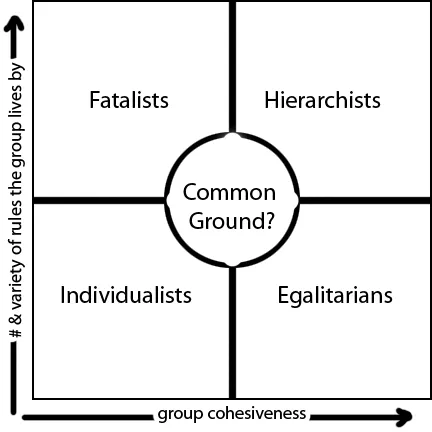

Each cultural style maps to a quadrant with one axis given by degree of groupness, i.e. boundary strength, with the other axis given by internal group structure or 'grid', so sometimes your will hear this called a grid-group theory.

It can look like this, where the biases are called rationalities:

Here are some others:

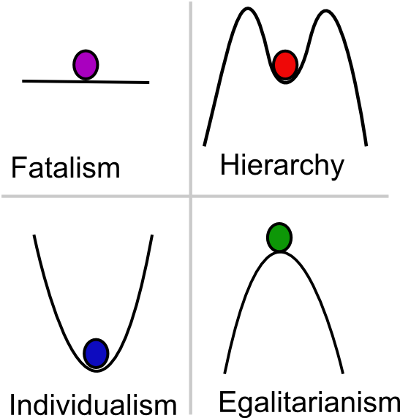

The curves reflect the bias in their, or rationality's, perception of risk (to 'nature' in this case, the shapes swap quadrants if it is about a risk to 'society').

Generally when people talk about the real world they are talking through their bias, or post hoc rationalisation.

For more discussion or introduction to this I suggest reading the links in the captions: fourcultures.com and www.dustinstoltz.com

The bulk of the early part of the book deal with this in reference to the failures of sociology and economics. So overall the book is a good introduction and great context for this way of thinking about our interactions, especially with regard to history, that is as a process of social events rather than its delineation by violent conflict alone.

What is not covered is why we seek to engage with others who differ from us, why are we driven to enter the arena and argued about it, or even just to implement institutions with minimal fuss. While separatism is always an option, why do we always return to each other, annoyed, joyful, and in duty, or is it true that money is only good because it keeps the kids in touch?

My own addition is that we have an urge to world which is most clearly seen when we should on each other (see why we should for my own recollection as fairy tale on this matter). The grid-group of four worlding cultures or biases or rationalities is a derivative outcome of the social urge to meet, have a bit of a thing, where we mix up our our attitudes, and linger late until it is early, and so in repetition, we norm the day somehow, into both institutions and law.

That is why we have a noyau, that is why we seek that arena out. That is why we dislike meetings more than anything but still persist in that endeavour. The 'dialectic' (of what ever stripe) is an outcome of that urge, and whatever arises dialectically is a derivative process of that urge. A urge which is evolutionary selected for, and where survival is barely rational, which is why bounded rationality as a model may still be too much rationality, to explain anything. Such that we a not Homo œconomicus nor Homo faber nor Homo fides nor Homo eros and definitely not Homo sapiens as all of these Homo sp. are worlding outcome-ish stereotypes, but perhaps best might be Aristotle's moniker πολιτικὸν ὁ ἄνθρωπος ζῷον, the busy-body biped.

Homo polis, to ignorantly mix my Latin & Greek, but unfortunately this use of city (polis) to indicate the behaviour excludes large areas of human geography and epochs of big history where this busy-body behaviour arose.

Douglas & Ney emphasise that these ideas of grid-group on bias and their perceptions of risk, allow one a space to reflect upon one’s own biases and preferences in relation to others, it allows a reflexivity of self and society, which will be of use to the social theorist. i.e. everyone. I would argue that it is actually more than that, and allows a pathway to a Pyrrhonist ataraxia, with or without the soteriological emphasis of salvation for the individual as self. It allows more, because it allows salvation of the self in the world, if not saving the world ‘itself’.

In the next part I will outline how things have changed in the last three decades, the references and examples or illustrations Douglas & Ney use to explain and discourse through the four cultural thought styles, and their preferred attendant institutions, just do not seem to work the way they did in the late 1900s.

References

Douglas, Mary, and Steven Ney. 1998. Missing Persons: A Critique of the Social Sciences, The Aaron Wildavsky Forum for Public Policy. Berkeley : New York: University of California Press ; Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-0-520-20752-3

‘A Short Summary of Grid-Group Cultural Theory’. 2010 [updated 2022] Four Cultures. Retrieved 21 December 2024 from https://fourcultures.com/a-short-summary-of-grid-group-cultural-theory/.

Stoltz, Dustin S. 2014, June 4. ‘Diagrams of Theory: Douglas and Wildavsky’s Grid/Group Typology of Worldviews’, Dustin S. Stoltz. Retrieved 15 February 2025 from https://www.dustinstoltz.com/blog/2014/06/04/diagram-of-theory-douglas-and-wildavskys-gridgroup-typology-of-worldviews/.

Crossposted at substack.com.

Postscript

I got an email asking about the "s" word. synthesis).

So I left a comment & substack note, as follows (edited):

I should have put "dialectic" in scare quotes, usually when I use the word I add that it can be some type of Vahalla where the dead rise again on the morrow to struggle again, Hegel/Marx synthesis or not, but here I was just using it to mean discourse as in arguing, chewing the fat and reckless gossip. I.E. More like how Peter L. Berger (part 2) uses it (his influence is quite big on us really). I think the Greek used it as a genre of discourse and not so much a structure of life, the universe and everything, and so both more specific, but not then overlaid over everything.

the urge to should is an urge to world, which is mostly a communication thing, a feeling for/to must-say-something

What i like about Douglas ideas is that it allows one to see what we say/do/prefer and should on others relates to our own perception of risk, and risk is a measure, or an index really, a pointer, we can use in reflexively looking at our own-positions-among-others, which ideologues never do

the center then cannot hold?

the world is the center and is always there (when we don't dialectic it all away in Vahalla), I think Douglas' mappings, as she says in Missing Persons at the end, allows for others when we place ourselves in the the world thereon therein thereof

remaining silent is not selected for in own evolution,