worlding in geelong July 2024 – very excited — part 1

Unable to make the opening night of the exhibition at Platform Arts of Worlding in Gelong|djilong I delayed the trip to the mainland into the penultimate week of the show (ending 19 July 2024). This did give me time to print and bind a doctoral thesis, which Dr Amber Smith kindly emailed to me. Along with the information that Amber was nearly nine months and about to world a baby.

I was excited because someone else was using the word ‘worlding’ in a very similar way to my own efforts. And had put together a show to promote it, to promote with it. I’ll write about the show directly some other time, and riff on reading Amber Smith's doctoral thesis.

Amber’s use of worlding in the thesis is framed by her Fine Arts degree and the usages of worldbuilding or worldmaking are being in the history of our collecting and arranging impulses, and in which the example of the Wunderkammer looms up just behind us, the prior art which informs so many of our institutions we consider to be part of our western enlightenment.

(gathering/collection/museum/gallery/curation/conserving/keeping/troving/honouring/hoarding/trophying/raiding/stealing)

The example of Wunderkammer provides an extra-long stride in the movement we have made since we first walked our bodies into landscape as country. A step in which the theology of the shrine, the crypt & cave or temple, church & chapel is secularised, only to become, in turn, an example of empire, wherein we must decolonise rather than secularise, in order to recover the sacred in the world. (Theology is a product of the late Roman empire's need to world ‘religiously’, theology is a type of colonisation. No, I do not have a doctorate in theology.)

Amber’s art’s practice is one of collecting and organising things. This is what we do in the world, that is how we self our lives, how we make a life, or build a family. The everydayness that Heidegger found suspect (like many 'artists' perhaps.)

An exhibition is a curation of things. Objects are a type of thing. (See these posts for my boosting of the word thing over object. Things meet into the world, objects not so much… —getting lost in the rabbit-holes of grammar as ontologies=theologies).

This is something continuously grappled with in my work, of containment and storage, visible and invisible, truth and fiction, the future being inetricably bundled up in the past (allegory comes along with us here too), and the endless contextual muddiness of the spaces that surrround the context of the collection.

Here Amber begins, I feel, to indicate that intimation of what I label the Janus ratio. Janus the jittering god of Roman thresholds is never far away from us, the movement that allows the contronym to arise in notice, splitting our attention in/out; where (self/world) becomes self and world: we come to agreed they be two different things, except in those narcissists who fail at the reality principle.

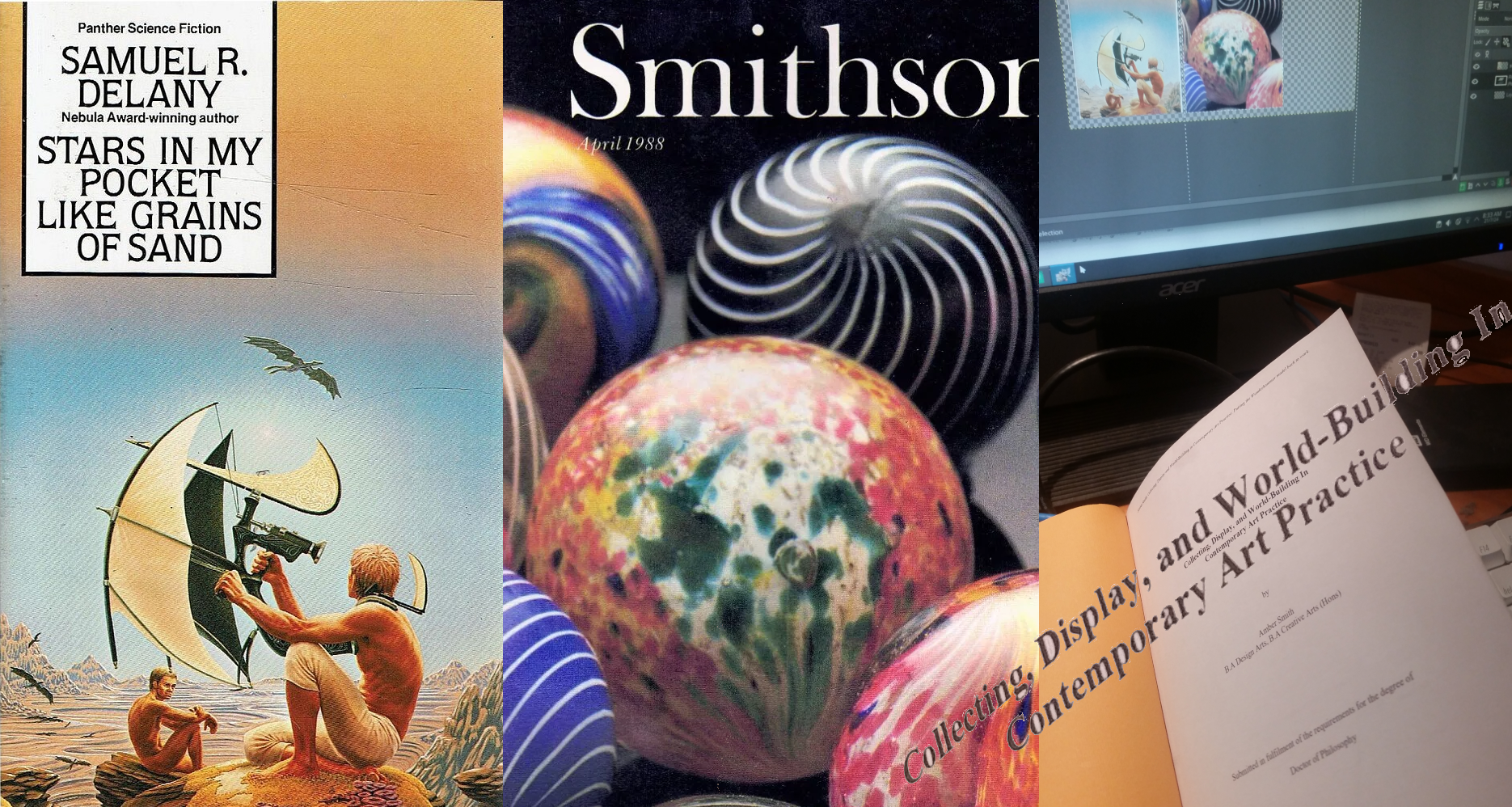

Later Amber saves her work from the 'muddiness' with the word constellation, a fine suspension in the liquid of our judgement. The stars are so far away, but everywhere in our night sky. The night is always close above our heads where we dream. The galaxy is a colloidal exuberance, like stars in my pocket.

I feel the need here to repeat my own path to the word worlding in this reading of Amber’s thesis (so I can get to the world as considering in the small frame of an exhibition in part 2).

It traces a certain history in collecting and explaining the world, in reference to the intensification of a Wunderkammer into modern museum and galleries, as world-building or world-making, then there are a bunch of continental philosophy writers made use of and more local art theorists, with a nod to SF writing and Donna Haraway.

This nod is my main starting place when I come to describe my journey to the gerund worlding from worldbuilding and world-making. If this was a doctoral thesis on SF then there would be less continental references. Know your audience.

When the newborn-baby world releases Amber a little I will try and organise an inteview in order to dissuss thesimilarities of movement we appear to have: world-building, world-making →worlding.

As a spoiler— I suspect that the key common condition is living in Australia, and listening to people on country.

For me, more recently, as the reading of SF was mostly a thing of my youth, I find both world-building and world-making (while also prior in my own "practice") now to be derivative forms. But then we always come late in any phylogeny, the POVerty of hindsight means our descriptions often begin with the last thing we saw, then we can re-trace our steps.

I arrived at worlding in amateur answers to questions of moral philosophy: "What is the ethical response to morality?"

Over a period of months in writing an essay for a competition, I replaced the ‘moral urge’ with the ‘world-building urge’. Urge here indicates a human-animal need to organise stuff, without there being any instinct as to what to do particularly, merely that something should be done!

And that we should this with others in negotiations (as things to do or to discuss) about things in the world now created by that very discussion. If both making and building are outcomes of that ‘urge’ then the key word then is world, and if that is a doing word, it is worlding.

Thinging is thus a type of worlding. Living is a type of worlding. Worlding is a type of selfing.

The self/world is a Janus dance of consciousness. The world is the self that does not see itself there, but feel it should… —should bother with the without as much as the within.

The world, to metphorically riff on Richad Dawkins' term, is an "extended phenotype" of psycho-social negotiation. And much like the self has little objective reality. Like the self the world is an illusion. The world does not exist, but we still feel we should should it into existence.

When we say that someone lives in their own bubble we hint at this greater place of bubbles absorbing bubbles, as the baby dyads into childhood with transitional objects, until the child’s world ruptures in empathy and discord with the ‘reality’ principle of everyones' body’s elses' bubble/s in the world, worlding their selves, selving their worlds, until death dusts our ashes over memories and their things, relic-ed in shrines or trophied in museums.

We collect ourselves together.

Back to the thesis at 2.3 World-Building, World-Making and Worlding. with some asides

I.E. some notes I made in the margins

Moves again from museums as worlds and as worlding efforts, through collecting as an art practice with references to the fictions of artists and writers, that obligatory Donna Harraway reference, then across briefly to gaming and then more ‘longingly’ to the algorithm, but there is an also a constant return to balance by way of the narrative arc to Amber’s practice in relationing anew in collecting —during covid. The self-fiction as world-fiction. And here thus the prior art is dealt with, in that continental frame arts based work cannot avoid.

In about 1986 Pete Spence said in introducing me to an audience at a poetry night in Melbourne that I ‘self-mythologised’. "We all do." I said.

But then to be more honest than glib, or at least annoying, I do not care about the worlding practice of 'the artist' or poets, or lawyers. They are all outcomes of what we all do regardless of what an economy or an empire allow us to do as tinker, tailor, spies. Everyone worlds, if an artists colonises this in the name of the Artist, we return to the theology of the priests and the artist vanishes into the Koonshirstabramović brand.

Side note: see post about Kristeva's alphabetical processions and Robert Graves: mythopoetics as an altered state.

One more thing. One more similarity. I read most of Amber’s thesis before we left Hobart, after binding it as a hardcover, and while in Deloraine on our way to the ferry to djilong/Geelong (pdf), and after buying Dent's Dictionary of Measurement Terms Terms, I walked up the main street as I do. It was cold I wore a soft shell and beanie. A young American said, “I like your hat.” I didn’t correct him, and said thank you as I had been taught to do. Then I realised as he quickly followed up with a question, “May I ask?” that he was a Mormon elder, “What makes you happy?” I kept walking, but slowed, and ummed and arhed and said, “walking”. He nodded. I saw the pair later, walking down by the river later pretending to dive off the sculpture strewn park into the winter browned river.

Samuel R. Delany. Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand. Bantam Books, 1984. [wikipedia]

Moore, Tom. Little Low Heavens : A Guide to Making and Enjoying Stonkers. 1994. Australian National University: Canberra [openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au, http://hdl.handle.net/1885/156041].

Smith, Amber. Collecting, Display, and World-Building In Contemporary Art Practice. 2022. Geelong/djilong: Deakin University.